|

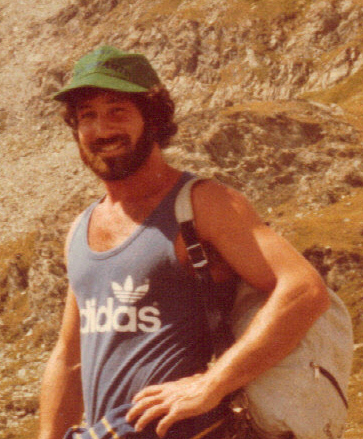

Tales of Travel Ibrahim and the

Syrians

It

was Norris

Basket’s brilliant idea to go to Syria.

This happened

in November of 1982, nearly two decades ago. Much has

I can still see my English pal gazing at our map in the flickering candlelight of a drafty Cappadocian cave, where we sat trying to figure out the best way to get to Israel.

My eyes followed his index finger as it drifted from our current stone-age accommodations in Central Turkey to the seaport of Mercin, from Mercin to the Turkish side of Cyprus, from Cyprus to Syria, from Syria to Jordan and over the Allenby Bridge into the heart of Israel. The trip looked like a snap on the map, but what trip doesn’t? On a map, you can cover hundreds of miles with an infinitesimal shift of the eyeball, the seas are as calm as Buddhist monks, all the roads are clearly marked and there are no morons with guns guarding the borders. In other words, maps are much different than reality. The truth was that Israel’s ongoing war in Lebanon had increased tensions in this part of the world, throwing the inherently mercurial Mediterranean ferry schedules into total disarray. So getting to the Promised Land on a low budget was no simple task. Yet I was young and still invincibly foolish. And Norris, who had a healthy measure of that indomitable sun-never-sets-on-the-empire fortitude, was no better. So we bused to Mercin on Turkey’s southern coast and ferried to Cyprus. At that point we discovered that we needed visas to go to Syria. We tried to procure them and were told we'd have to go to Istanbul to get them. That was simply too far out of our way, so we boarded the ship to Syria without visas.

After a half-year on the road, I’d developed a lot of faith in whatever god protects boneheaded travelers. But this time – as an American Jew landing visaless in a hostile, totalitarian Arab state – I was kind of pushing it. When we docked in Latakia, the customs officials couldn’t seem to digest the fact that we didn’t have visas. They called over other men in uniforms who called over others until we had a crowd of swarthy, mustachioed faces all around us, jabbering away in a mixture of Arabic and English. One senior-looking official said that we were going to jail unless we could produce visas. But an even higher official finally settled the matter by pulling us aside and explaining that we could purchase special “port” visas – good until the next ferry left – for $50 cash apiece. Since we only had about $100 between us and still needed to buy ferry tickets, the special visa rate was discounted accordingly. Once cleared to proceed, Norris and I wandered into town to secure sea passage to anywhere. Latakia was a less than memorable city. I do recall a lot of four- and five-story gray stone buildings lining broad dirty boulevards. Drivers were crazy and car horns incessant. Minarets popped up here, there and everywhere, and a tea shop graced every corner, most filled with men smoking and slapping around gaming tiles. Like other Muslim countries, there weren’t many women out and about. The men were mostly dark, thin and wore mustaches like their leader-for-life, Hafez Assad. He was still very much alive back then, wielding enough influence to have his likeness hanging in every shop window and from every lamp post. As obvious strangers in town, Norris and I attracted a lot of interest. I was surprised to find that many of the Syrians spoke English. One was even wearing a “Who shot J.R.?” t-shirt. I was less surprised to discover that they unilaterally hated Americans. I was routinely frowned at and chided until I wised up, changed my accent and claimed to be British, which seemed to work for Norris. My friend and I soon discovered that we couldn’t get tickets on the next ferry out of Latakia because it was a Greek ship and we had Turkish stamps in our passports (don’t ask). A more hospitable Russian ferry was leaving for Alexandria in two days, so we bought tickets and walked back to the port praying that the customs officials would let us hang around till then. They weren’t pleased, but extended our special port visas at no extra charge. We were confined to the main hall of the customs building, a glass and steel structure that resembled an airline terminal. It was brightly lit with marble floors, black vinyl lounges, sand-filled cylindrical ashtrays and banners of President Assad hanging from every rafter. The building closed at dusk, so we were left alone to eat oranges (our only food), play cards and idly chat about girls, travel and all kinds of food (except oranges). Long past dark, I heard the squeaking sound of sneakered feet on marble coming from an unlit corridor. A figure emerged. It was the graveyard shift security guard making his rounds. Unlike graveyard shift security guards in America, this one wore combat fatigues and had a machine gun slung over his shoulder. On his head, and wrapped around his face, was a black and white kaffiyeh like the kind Yasser Arafat always wore. The kaffiyeh hid all of the guard’s features except his eyes, which seemed to appraise us the way a snake might appraise two mice. He and his reptilian eyes circled us slowly, his sneakers no longer squeaking. As he drifted behind us, he slipped the machine gun from his shoulder and slammed a cartridge of ammo into the breach. Uh-oh, I thought, suddenly wishing I’d listened to my parents and continued my fledgling sports writing career instead of taking a couple of years off to travel. The guard completed his circle and stood before us, his weapon leveled. His creepy eyes examined Norris and me, back and forth, forth and back, until they finally settled on me. He took two steps forward, poked me in the gut with the gun nd snapped, “Pass-a-port.” I dug it out of my pocket, handed it over and instantly saw a measure of hate swirl in his eyes. “You American?” he growled. I nodded and tried to swallow. My adam’s apple felt as big as a cantaloupe. “In Lebanon, soldier shoot me here with American gun,” he said, patting his side. “It is last he do. I...” He motioned how he blew the guy away, trilling machine gun effects with his tongue. “Maybe I shoot you. Or maybe I...” he ran his index finger across his throat. “...cut you when you sleep.” I was speechless. But Norris wasn’t. “Now look here,” he objected boldly. “He didn’t shoot...” My pal’s boldness evaporated as soon as he felt the machine gun muzzle pressed under his chin. “I’m...uh...British,” Norris muttered. The guard brought his unoccupied index finger – the one not poised on the trigger - to where his lips lurked beneath the kaffiyeh, and hissed at Norris to be quiet. Then he took a couple of paces back and leveled the gun like he meant business. I really thought that this might be curtains for us. Curiously, my fear seemed to vanish. There was nowhere to run, nowhere to hide, nothing to do but accept the inevitable. The guard gave a war whoop and jerked the gun to his shoulder. Then he spun it around in his hands like a propeller, flipped it under his arm, across his back, around his waist and snapped it adroitly into firing position at his hip. He paused momentarily, then launched into another set of parade maneuvers, which he finished with a muted click of his sneakered heels. Norris gave him a sarcastic two or three clap ovation. Not knowing quite what to do, I picked up three oranges and put on a show of my own. I started juggling, doing tricks. I threw one under my leg, another behind my back... The guard was watching me, his gun now slung loosely over his shoulder. I tossed an orange to him. He caught it. I motioned for him to throw it back. He did, and I started juggling again off his throw. He swept the kaffiyeh from his face. I was surprised to see he was just a kid, 16, maybe 17 years old. “You teach me,” he said, pantomiming the juggling motion. I shook my head. “You teach me,” he repeated. I shook my head again. “Why you no teach me?” he asked, somewhere between angry and hurt. I ran my index finger across my throat. “Why should I if you’re going to cut my throat later?” “No, no,” he replied, dismissing the threat with a wave. “I make joke.” He cracked a culture-bridging grin. “You teach me now?” So I spent my first night in Syria teaching young Ibrahim the basics of juggling. Then I taught him some card tricks. Meanwhile, our artist in residence (Norris) sketched a nice, complimentary portrait of his face, darkening his adolescent peach fuzz into a beard stubble any Muslim warrior would be proud to call his own. Ibrahim was delighted and as he finally left us to finish his rounds, he promised not to cut our throats unless it was absolutely necessary. The next day, Ibrahim returned while off-duty to bring us all kinds of food, including more oranges, pita bread, hummus and tasty fried balls we would later discover to be called falafels. He spent the night “guarding” us instead of making his rounds, practicing juggling and card tricks, and asking countless questions about America. Actually, he asked countless questions about the girls in America. The rest he wasn’t much interested in. Finally the morning of our departure broke and the customs chief ordered Ibrahim to escort us to the Russian ferry. With the kaffiyeh wrapped around his face, Ibrahim once again looked like a hardened warrior. But when we arrived at the gangway, he hugged both of us, his machine gun muzzle poking me in the ear. And those cold, cruel, anti-American eyes of his turned soft when he wished us farewell. “Ma’a el salama,” he said. “Go in peace, friends.” changed since then. Even more has remained the same. A vast majority of people in the world still want to live in peace, but we’re all susceptible to the will of warmongers who use prejudice and ignorance to fan the fires of hate. Although we are sometimes forced to defend ourselves with force, we must always remember – as I learned during my brief stay in Syria – that there’s a thin line between “enemy” and “friend.” Reading Room Outer Space Art Gallery  Eat to live with Isagenix, the food of the future. Cleanse your body, lose weight and feel great! |